H Sadeghi-Nejad, P Ilbeigi, SK Wilson, JR Delk, A Siegel, AD Seftel, L Shannon and H Jung

Infection is a devastating complication of penile prosthesis surgery that occurs in approximately 2–5% of all primary inflatable penile primary implants in most series. Prevention of hematoma and swelling with closed-suction drains has been shown not to increase infection rate and yield an earlier recovery time. Despite the intuitive advantages of short-term closed-suction drainage in reducing the incidence of postoperative scrotal swelling and associated adverse effects, many urologists are reluctant to drain the scrotum because of a theoretical risk of introducing an infection. In conclusion, this study was undertaken to evaluate the incidence of infection in threepiece penile prosthesis surgery with scrotal closed-suction drainage. A retrospective review of 425 consecutive primary three-piece penile prosthesis implantations was performed at three institutions in New Jersey, Ohio, and Arkansas from 1998 to 2002. Following the prosthesis insertion, 10 French Round Blake (Johnson & Johnson) or, in a few cases, 10 French Jackson Pratt, closed-suction drains were placed in each patient for less than 24 h. All subjects received standard perioperative antibiotic coverage. Average age at implant was 62 y (range 24–92 y). Operative time (incision to skin closure) was less than 60min in the vast majority of cases. There were a total of 14 (3.3%) infections and three hematomas (0.7%) during an average 18-month follow-up period. In conclusion, this investigation revealed that closed-suction drainage of the scrotum for approximately 12–24h following three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis surgery does not result in increased infection rate and is associated with a very low incidence of postoperative hematoma formation, swelling, and ecchymosis.

International Journal of Impotence Research (2005) 17, 535–538. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901354; published online 23 June 2005

Keywords: penile prosthesis; erectile dysfunction; complications

Introduction

The need to drain the scrotum has remained a controversial subject in penile prosthesis surgery. Drain proponents argue that decreased hematoma formation and increased patient comfort warrant routine scrotal closed-suction drainage. In contrast, to avoid dreaded prosthesis infections, drain opponents cite the possibility of increased infection risk secondary to retrograde migration of bacteria. These physicians state that a good compression dressing will minimize hematoma formation.1 Hence, the question: why subject the patient to a higher infection rate? Regardless of an individual surgeon’s personal preferences, a search of the medical literature reveals that this latter rhetorical question has not been adequately addressed. Are infection rates actually higher when the scrotum is drained after penile prosthesis surgery? The current study was undertaken to answer the question through a multi-institutional investigation and to evaluate the rate of infection when closed-suction drainage is employed routinely in trans-scrotal three-piece penile prosthesis surgery.

Materials and methods

Between January 1998 and 2002, 425 consecutive patients underwent primary implantation with a nonantibiotic-coated, nonhydrophilic, inflatable three-piece penile prosthesis (Mentor alpha 1 or AMS 700) by five primary surgeons at three medical centers in New Jersey, Arkansas, and Ohio. All patients had a diagnosis of organic erectile dysfunction with etiologies including diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, radical pelvic surgery, radical retropubic prostatectomy, pelvic radiation, or Peyronies’ disease. Every patient received standard perioperative antibiotic coverage with fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and/ or vancomycin. The surgical fields were prepared with the customary 10-min scrub wash, followed by insertion of a closed urethral catheter drainage system. The procedures were performed using the same technique with vertical or transverse scrotal incisions. Following the implant, all patients received a 10 French closed-suction drain (Round Blake (Johnson & Johnson) or, in a fewer instances, Jackson Pratt), along with partial cylinder inflation (70%) for approximately 12–24 h postoperatively. The drains and urethral catheters were removed and the prosthesis was deflated on the first postoperative day. The mean follow-up was 18 months with a range of 12–36 months.

Results

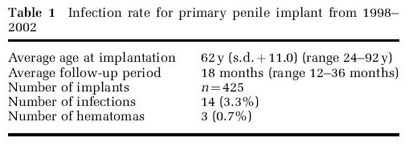

The average age at prosthesis implantation was 62 y (range 24–92 y). Average operative time, defined as incision to skin closure, was less than 60 min in the vast majority of cases. Table 1 outlines study demographics including infection and hematoma rates. Overall, there were 14 (3.3%) infections during an average 18-month (range 12–36 months) follow-up period. There were 3 (0.7%) cases that developed hematoma despite drainage in this cohort.

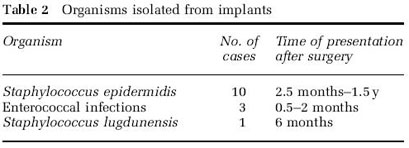

Among the infected prostheses, 10 patients grew Staphylococcus epidermidis from their cultures. These patients presented 2.5 months to 1.5 y after the implantation, with an average of 6.25 months postoperatively. Enterococcal infections accounted for three cases presenting at 0.5–2 months. There was one case of Staphylococcus lugdunensis infection that presented 6 months postimplantation. Interestingly, there were no Staphylococcus aureus, bacteroides, or pseudomonas species isolated as reported in some other series.

Salvage prosthesis procedure was performed in eight of the 14 patients presenting with infection. Two of the salvaged prostheses were eventually removed because of subsequent reinfection. In six patients, explantation without salvage was thought necessary because the initial presentation was that of a toxic, virulent infection.

Discussion

Penile prosthesis infection is a distressing and dreaded complication of prosthesis surgery. Infections occur in approximately 2–5% of all primary inflatable penile implants.2–4 Predisposing factors include local and remote infections, immune status of the patient, presence of prolonged urethral catheters, edema and ischemia of the corpus cavernosum, and hematoma formation.3–5 Although postsurgical scrotal drains have been implicated in developing prosthetic infections, they have not been exclusively studied in the urological literature. The routine use of closed-suction drains, however, has been extensively investigated in other surgical arenas.6–10 Kim et al8,9 prospectively looked at patients undergoing bilateral total hip and knee arthroplasties in order to assess the effect of shortterm postoperative drainage on wound healing and infection. They were not able to show any correlation between wound infections and use of closedsuction drains. These authors reported a significant difference, however, with respect to drainage from the wound with required dressing reinforcements, ecchymosis and erythema about the wound, and hematoma formation in the group without drainage. They concluded that since there was no added risk of prosthesis infection, the routine use of closedsuction drains is beneficial in order to decrease wound swelling, hematoma formation, and to lessen the psychological impact from the patient’s fear of swollen surgical sites.

We suggest that a similar inference can be made in penile prosthesis surgery. In our series, 425 consecutive patients underwent primary insertion of three-piece inflatable prosthesis by five primary surgeons at three different institutions. All subjects had histories consistent with an organic etiology for erectile dysfunction, including peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, radical pelvic surgery, radical retropubic prostatectomy, pelvic irradiation, and Peyronie’s disease. The patient profiles, surgical techniques, and prosthesis devices were similar at all three institutions. The overall infection rate in this cohort was 3.3% (14/425), which is similar to infection rates reported for three-piece penile prosthetic surgery.2,3 Recent reports on the efficacy of antibiotic impregnated inflatable penile prostheses indicate infection rates as low as 0.68% after 180 days.11 It should be noted that while all surgeons in the current publication have switched to using the antibiotic-coated or hydrophilic penile prosthesis substrate-coated devices, the prostheses used in this reported series were the nonantibiotic-coated AMS and the nonhydrophilic Mentor Alpha 1 inflatable devices. A publication on patient satisfaction and device reliability of the nonhydrophilic Mentor Alpha 1 inflatable penile prosthesis in 1994 corroborates our finding of low infection rates with routine uses of closed-suction drainage. Garber12 reported only one periprosthetic infection in a series of 50 cases (2%) that were routinely drained with a closed-suction drain for 24 h (2–41-month followup).

There were 3 (0.7%) patients that developed scrotal hematomas despite drainage in our cohort. A required technical step in penile prosthesis surgery is the need for bilateral corporotomies for insertion of the prosthesis cylinders inside the corporal bodies. When inflatable three-piece devices are employed, small openings (corporal exit sites for the tubing that will be connected to the pump) into the scrotum may become a source of corporal bleeding and hematoma formation. This is true despite meticulous closure of the associated corporotomies. As a result of this inherent and unavoidable part of the technique, some patients are subjected to accumulation of postsurgical fluid and blood that contributes to additional discomfort, swelling, and hematomas. Although closed-suction drainage would not be expected to eliminate the problem in all cases (ie, due to suction malfunction or blockage), most experts would agree that the incidence of hematoma formation, ecchymosis, and scrotal swellings would be less if drains are used. The overall scrotal hematoma rate during undrained penile prosthesis surgery has been reported to be around 2.9%, whereas cases that were drained in the same series had significantly reduced hematoma rates (0.9%) without an increase in infection rate.13 Short-term scrotal drainage with partial cylinder inflation following trans-scrotal three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis surgery was therefore employed in order to enhance patient comfort and satisfaction by reducing postoperative swelling, ecchymosis, and hematoma formation. Survey of one author’s (SKW) databank (over 4000 cases) revealed a significantly increased infection rate of 17% when hematomas were incised and drained postoperatively. It is inferred that in penile prosthesis surgery, whenever possible, postoperative hematomas should be managed expectantly rather than with incision and drainage. Although the current series does not address revision cases, the authors routinely drain the scrotum in revision inflatable penile prosthesis surgery cases as well. It is hypothesized that capsule neovascularity without muscle support may further predispose revision cases to hematoma formation.

Retrograde travel of microorganisms through the drain outlet is a real concern and drain opponents argue that retrograde migration of bacteria places penile prostheses at a higher risk of infection.1 Organisms can travel both ways within the lumen or on the outside of the drain tubing.14 Raves et al14 have shown that with simple conduit drains, retrograde migration of bacteria occurs with relatively high frequency (75–90%) within 72 h. With closedsuction drains, however, the frequency was much lower (20%) during this time interval. Early removal (o24 h) of the Jackson-Pratt drains in the same series revealed an absence of retrograde infection. In this cohort, all drains were removed within the first 24 h following surgery. The passage of organisms may be impossible to prevent, but can be minimized by avoiding large incisions in the skin that leave an open wound surrounding the drain. Drains should not be brought out through the main incision since the incision may become infected by the drain or allow organisms already in the wound to enter the cavity of dissection. 14 It is recommended that the drain incision be of lesser caliber than the actual diameter of the drain, but not so small that it compresses the drain.

The majority of the species isolated from the infected cases in our series were S. epidermidis and in keeping with other publications indicating this organism as the most commonly isolated species in infected cases, accounting for 35–80% of all positive cultures.15,16 Table 2 lists the organisms isolated from the implants in the infected cases. Enteroccocal infections, isolated from three of the 14 infected cases in our series, have been reported as causative organisms in various periprosthetic infections and were responsible for six of 32 hip prosthesis acute infections in a recent orthopedic series.17 S. lugdunensis is less frequently reported as the causative organism in periprosthetic infections and the pathogenetic mechanisms leading to infections by this organism are unknown.18 This species is a coagulase negative Staphylococcus first described in 1988 and appears to share virulence determinants with S. aureus. It has been reported as a causative pathogen in a range of nosocomial infections, including endocarditis, polymer-associated infections, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, UTIs, and wound infections.18

Conclusion

Closed-suction drainage of the scrotum after penile prosthesis surgery is employed to minimize the chances of scrotal hematoma formation in the postoperative period. This retrospective multiinstitutional investigation demonstrates that shortterm closed-suction drainage following three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis surgery appears to be safe and effective without a demonstrable increased risk of prosthesis infection. Future randomized, controlled studies using the newer hydrophilic or antibiotic-coated prostheses are needed to firmly establish safety and efficacy of drainage with these newer devices.

References

- Magee C et al. Potentiation of wound infection by surgical drains. Am J Surg 1976; 131: 547–549.

- Montague DK. Periprosthetic infections. J Urol 1987; 138: 68–69.

- Montague DK, Angermeier KW, Lakin MM. Penile prosthesis infections. Int J Impot Res 2001; 13: 326–328.

- Sadeghi-Nejad H, Seftel A. Vacuum devices and penile implants. In: Male and Female Sexual Dysfunction. Elsevier/ Mosby: St Louis, Missouri, 2004.

- McClellan DS, Masih BK. Gangrene of the penis as a complication of penile prosthesis. J Urol 1985; 133: 862–863.

- Saleh K et al. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res 2002; 20: 506–515.

- Morris AM. A controlled trial of closed wound suction. Br J Surg 1973; 60: 357–359.

- Kim YH, Cho SH, Kim RS. Drainage versus nondrainage in simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13: 156–161.

- Kim YH, Cho SH, Kim RS. Drainage versus nondrainage in simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; Feb (347): 188–193.

- Parker MJ, Roberts C. Closed suction surgical wound drainage after orthopaedic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 4: CD001825.

- Carson Jr CC. Efficacy of antibiotic impregnation of inflatable penile prostheses in decreasing infection in original implants. J Urol 2004; 171: 1611–1614.

- Garber BB. Mentor Alpha 1 inflatable penile prosthesis: patient satisfaction and device reliability. Urology 1994; 43: 214–217.

- Wilson S, Cleves M, Delk JI. Hematoma formation following penile prosthesis implantation: to drain or not to drain. J Urol 1996; 55: 634A.

- Raves JJ, Slifkin M, Diamond DL. A bacteriologic study comparing closed suction and simple conduit drainage. Am J Surg 1984; 148: 618–620.

- Carson CC. Infections in genitourinary prostheses. Urol Clin North Am 1989; 16: 139–147.

- Abouassaly R, Montague DK, Angermeier KW. Antibioticcoated medical devices: with an emphasis on inflatable penile prosthesis. Asian J Androl 2004; 6: 249–257.

- Soriano A et al. Treatment of acute infection of total or partial hip arthroplasty with debridement and oral chemotherapy. Med Clin (Barc) 2003; 121: 81–85.

- Von Eiff C, Peters G, Heilmann C. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2: 677–685.